- 10.0Cover

- 10.1Ghost PopulationsInes Doujak

- 10.2How to Read this Broadsheet

- 10.3BluntRinaldo Walcott

- 10.4COVID-19, Language, and IdentityAi Taniguchi

- 10.5Finding LanguageVanessa Dion Fletcher

- 10.6The Abundance and Conflict of On-Demand WritingLouise Hickman

- 10.7UnlanguagingJesse Chun

- 10.8An Infinity of TracesMatt Nish-Lapidus

- 10.9Speaking Out: Researchers on Pandemic-Era HealthcareZoë Dodd, LLana James, Laura Rosella

- 10.10Living ScoresOana Avasilichioaei

- 10.11Pronouncing (Un)FreedomShama Rangwala

- 10.12blertJordan Scott

- 10.13In Protest and Choir SongMaandeeq Mohamed

- 10.14In Support of the CensureJacob Wren

- 10.15Glossary

The Abundance and Conflict of On-Demand Writing

- Louise Hickman

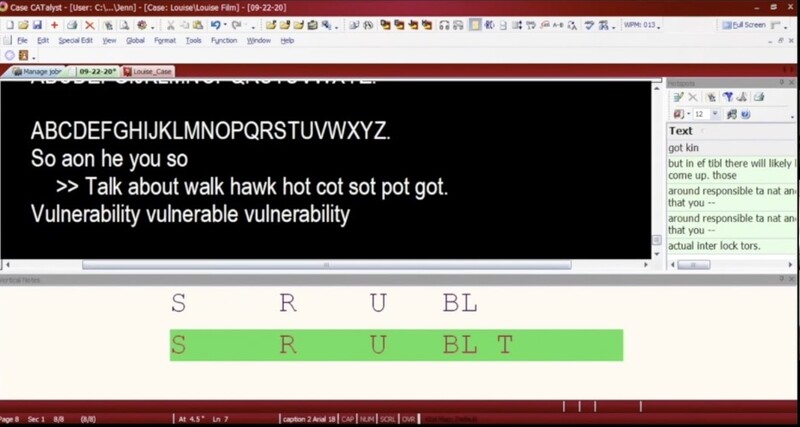

Figure 1: Image Description: A coloured screenshot of stenographic software used by real-time writers to produce captions. The image is taken from the short film “Captioning on Captioning” (2020) by Louise Hickman and Shannon Finnegan. The screen is split into three areas, left to right, black background with the output of the captions as they appear to readers, the next box displays a possible outcome connected with steno input, the third area, located at the bottom, contains the raw data (steno brief).

A-BG S PR: Access is practice

[possible conflict]

A-BG S PR: Access is approximate

A-BG S PR: acknowledge is proximate.

The ubiquity of the QWERTY keyboard has been established since the late nineteenth century. The stenography machine emerged shortly afterwards but with only 24 keys compared to the 100 keys of a standard board. The steno keyboard is designed to employ multiple keys in concert (also known as chording) to produce letters, words, and even small phrases with a singular stroke. In the last thirty years, the legacy of captioning is increasingly bound with the growing demands of accessibility for disabled and d/Deaf readers. Those histories are shaped by stenographers, their technical expertise, disability rights legislations, feminist labour, and the growing demand for real-time technology. Quite often these histories are rendered invisible when accessing captions onscreen in our everyday interactions. To capture the multiplicity of captioning work, this essay has woven together previous conversations with Kevin Gotkin (New York–based disability arts organizer) with the documentation of steno shorthands. The conversation between Kevin and myself took place at the Het HEM gallery in the Netherlands in June 2021. Our conversation brought together a range of themes relating to the abundance of access, access work, and the practice of captioning. This essay adopts a performative approach to surface the shifting tensions between the abundances and demands of cultivating accessible spaces. Here, “tension” refers to the many challenges faced by stenographers when capturing conversations under real-time conditions as opposed to closed captions. To cope with these challenges, writers work with their stenographic software to build a personal dictionary that can avoid the doubling up of similar steno shorthands. When similar shorthands appear in a stenographer’s dictionary this presents conflicts for their real-time work.

>> Real-Time writing

The first real-time shorthand machine (see Figure 3) was introduced in 1988 in the United States. The clunky cream machine was roughly the size of a personal desktop computer, thus restricting the mobility of the user. This particular machine, known as the Digitext ST (Steno Translator) also lacked the capacity to offer onboard readback of their written work. In the early 1990s, the increasing significance of real-time writing applied additional pressure on stenographers to become more efficient and mistake-free. The reality of real-time writing for many writers meant training their dictionaries to be conflict-free to ensure the systematic output of readable text. The expectation to perform complex cognitive tasks under real-time pressure is analogous to writers becoming the machine themselves: establishing the process(es), performing the process with no errors, all while remaining emotionally and socially removed from their work. An autonomous dream? A nightmare? That would be another paper. The question remains: is it possible to cultivate a feminist practice that allows and forgives human-made mistakes in access work?

>> Steno-brief

An example of a conflicting steno-brief might look like this:

A-BG: access

A-BG: academic

A-BG: accusation

This is an example of a steno-brief (A-BG) whose inputs have a range of possible meanings for the writer, which they must overcome and code according to their embodied relationship to their machine and dictionary software. Here is another example:

PHA: machine

PHA: mental anguish

PHA: parole

To avoid these conflicts, stenographers (also known as real-time writers or CART operators) are always working in relation to their machines to pair and repair their text output with the spoken language around them. As a result, these conflicts are very much shaped by the particular ways that writers embody their writing machines.

A-BG PHA: access machine

WR-G PHA: writing machine

TKA PHA: data machine

Is a stenographer an access machine? A transcriber? A disinterested observer of information? A translator of great ideas? In my work, I position the practice of captioning within the histories of feminist labour. The coding of spoken speech, the mass documentation of phonetic shorthand, and the development of stenographic technology were originally highly gendered labour practices whose conception can be dated to midcentury office work.

KA-PG S PO-L -EBG: captioning is a political economy.

For unfamiliar readers, the distinctions between genres of captions are not immediately recognizable, as they can include closed captions (added to media content), real-time captions (live broadcasting and events), open captions (embedded in media content), and live transcription (automated). Captions are seldom examined in their own right as a cultural object because they are often seen as peripheral, collapsed into a byproduct of accessibility.

KA-PGZ -PB PHA-EUBG: captions are not magic

[possible conflict]

KA-PGZ -PB PHA-EUBG: capacity are not magic

>> The practice of “access work” in cultural institutions is more than adding a ramp.

During our conversation at Het HEM this past summer, Kevin articulated how access too often remains an afterthought: “Cultural institutions tend to have chaotic notions of accessibility, typically understood in terms of compliance, and set apart from matters of artistry.”

KAO-BGT PW KPHR-PBS: chaotic and compliance

[possible conflict]

KAO-BGT PW KPHR-PBS: correct and common sense

We read technical, embodied, and bureaucratic forms of captioning—from invitations and invoices to software and methods—as a way to perceive access as an ongoing interrogation; as a practice. Our goal is to dislodge access practices from their usual relegations and study them the way we would do other artistic processes.

>> Can we practice access without conflict?

My conversation with Kevin took place in the context of Chapter 4OUR: Abundance, an exhibition curated by Simon(e) van Saarloos and Vincent van Velsen that sought an escape from the extractive and commodity-centric logic of scarcity. As Simon(e) wrote in their essay for the show:

“Abundance is the wealth of presence: those who always have been around ...This isn’t a one-off performance, or an alternative arts fund, or a separate month or a special day a year to celebrate our existence – we claim the stages upon which we’re already standing as the stage … We are already out and wild, dancing, whispering, and shouting. We drift, we observe and listen with abundant attention, offering a concentration not based on selection, comparison, and hierarchical validation.”

[possible conflict]

A-UBDZ: Abundance

A-UBDZ: Objected

A-UBDZ: Observed

What are the possibilities of crip notions of abundance? That is, what are ways of assessing needs and resources that are anchored in disability culture and community? One of the ways I’ve decided to focus my work is by examining the political economy of access work. Access work includes many things, but we might most readily recognize it in the labour of sign language interpreters or audio describers who make verbal translations of visual material.

>> Access is data

>> Data is access

A-BG S TKA: access is data

TKA S A-BG: data is access

In the Netherlands, the local context at Het HEM gallery, to access sign language support, real-time captioning, and deafblind interpretation, Dutch citizens must provide audiometry (medical documentation of “hearing loss”) of their hearing levels and have access to a central database of access workers who can be paid directly by Dutch funds for deaf and deafblind residents.

Upon the completion of these tasks, there is a public subsidy of 30 hours per year of interpreting for private situations (outside of education and work). The allotted time increases to 168 hours for deafblind people.

H-EL TK-GS: medical documentations

[possible conflict]

H-EL TK-GS: health diagnosis

Access is a political economy.

A-BG S PO-L -EBG: access is a political economy.

Dutch not-for-profit organizations can apply for subsidized support for interpreting hours if they can demonstrate service to multiple users at once.

S-D TPO-R K-PL -BL: Subsidy for Community Building

The dialogue between the readable text (as a proxy for spoken speech) and the steno shorthand, including the possible conflicts between the briefs themselves, draws attention to the care and expertise needed to build access. More than merely inserting inputs into a machine, the stenographer never stops interpreting a discursive context to mediate the relationship between spoken and written text, which contains a vast variety of possible meanings. Transcribers, we might say, work with the conflict immanent in interpretation. It is not their capacities (and the limits to them) that restrict how users can engage through access technologies. Rather, the weight of bureaucratic actions and structures of scarcity limits the economy—and the abundance—of language participation for certain users.

See Connections ⤴