Ornamenting Relation features five artists from different cultural and aesthetic locations— Hamra Abbas, Golnar Adili, asmaa al-issa, Azadeh Elmizadeh, and Ayesha Singh. Together, their artworks develop an architecture of ornament and relation that can be accessed through three organizing intuitions: The Grammar of Ornament, The Golden Thread, and Relation. Beyond these, the audience of this series is invited to exercise their own interpretive methods to this ornamental archive in the making.

Intuition #1: The Grammar of Ornament

Owen Jones’s The Grammar of Ornament (1856) is a printed compendium translating all the world’s ornaments for the pleasure and education of its British reader. Ornamenting Relation applies contemporary critiques and politics to this colonial repertoire to reorient its cultural relevance. While the nineteenth-century project is embedded in the imperial grammar of categorization and appropriation, this exhibition is rooted and routed through veils of opacity and a golden thread that is unruly within its own teleology.

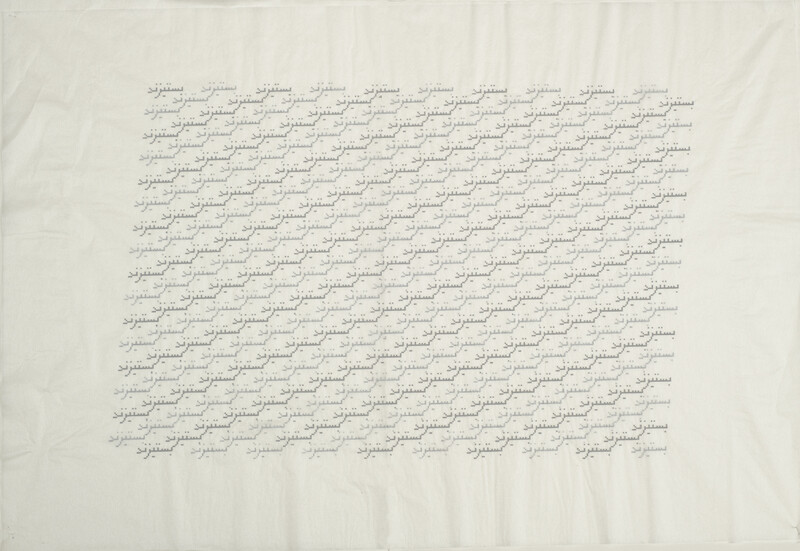

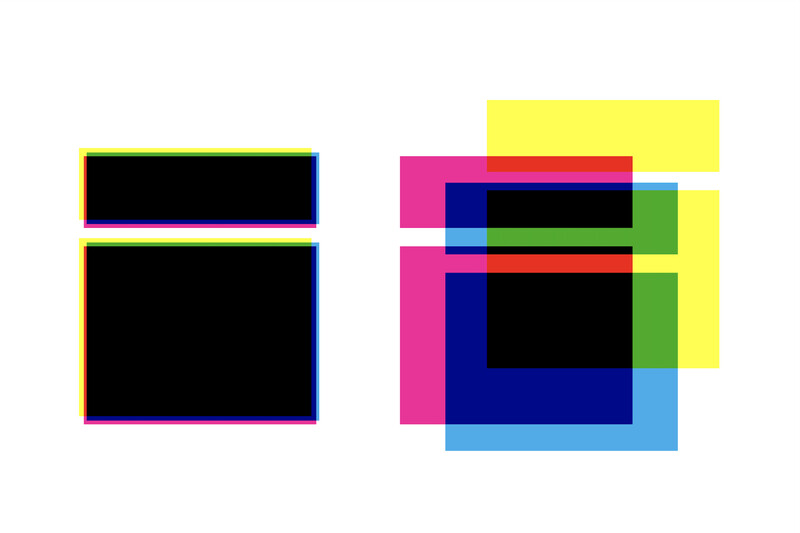

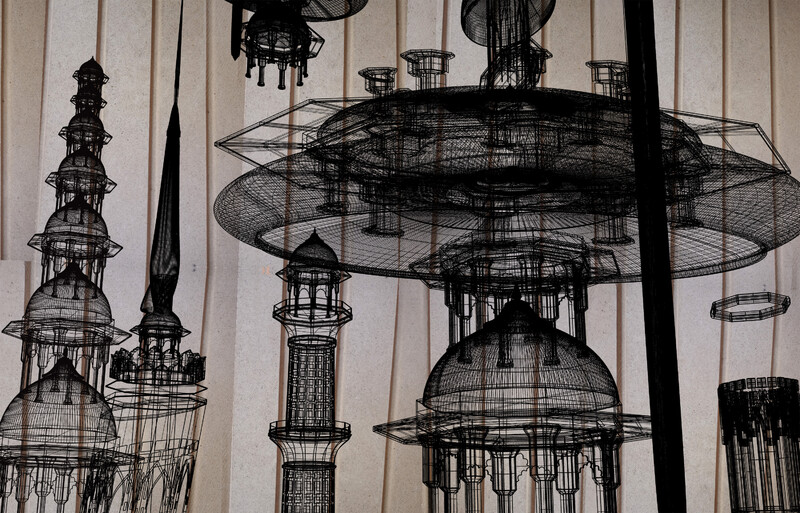

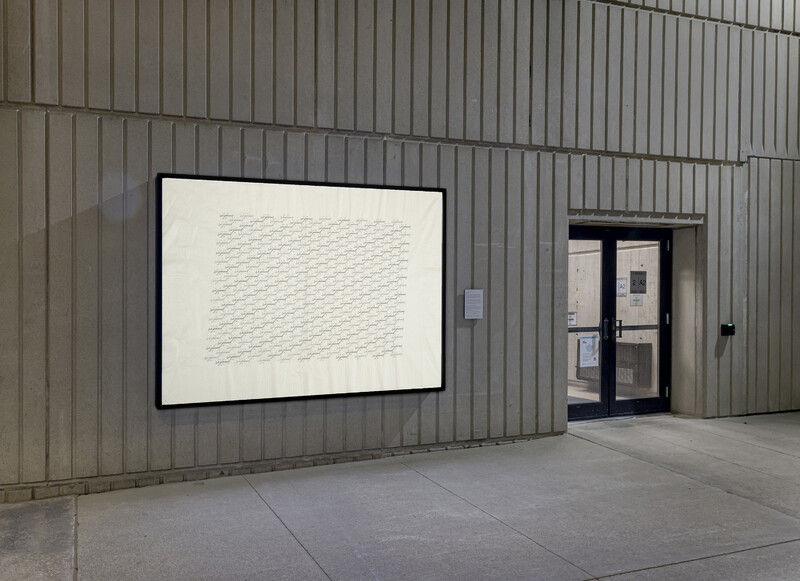

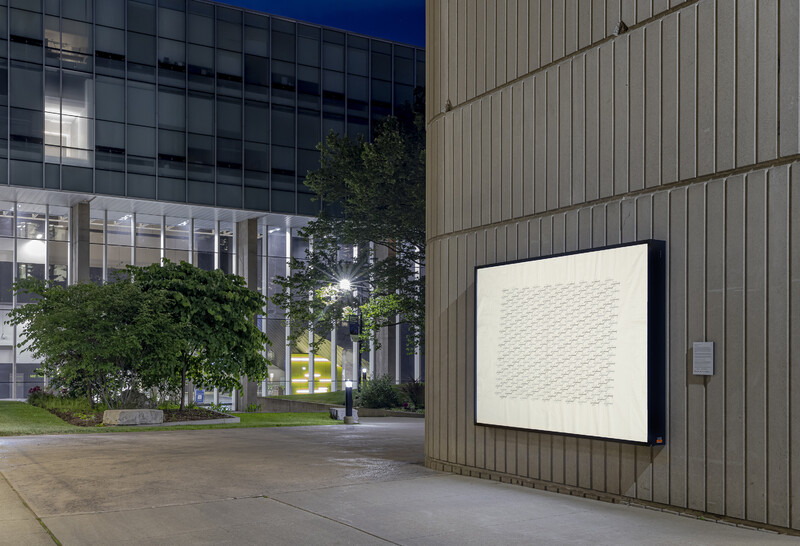

Centering the ornament in this series is to revitalize it as a field of artistic and cultural practice, while expanding its forms of communication. Each lightbox offers different ways of reading the ornament. They include geometric, architectural, painterly, and textual references that represent different artistic ways of ornamentation. Hamra Abbas’s Kaaba Picture as a Misprint depicts a geometric distortion of the most sacred site of Islam, a site of both pilgrimage and nostalgic return. Architectural forms in the work of Ayesha Singh attain more readability: iconic motifs of Mughal structures in India are recognizable despite their hybridized and amalgamated forms. Azadeh Elmizadeh’s work is situated between abstraction and representation in that it obscures figures in a battle scene, commonly depicted in the Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp. The figures and their actions retain their relational energy in the heat of battle, even as they are effaced and made esoteric through painterly ornamentation. Finally, Golnar Adili’s Bestizand (They Quarrel) evokes binaries—of decoration and function, translation and opacity, textual and visual—that further explodes the ornament into the realm of possibility through articulation and refusal.

Intuition #2: The Golden Thread

The final artist included in Ornamenting Relation is asmaa al-issa, whose work is presented as a Respondent Program. Our recorded conversation about the decorative and relational impulse in her work can be viewed below. Of note is the latency of intuitive research in her own work, which is best illustrated by her consistent use of golden threads. The golden thread concept was first introduced to the artist by a professor in Comparative Religions, who envisioned it moving through all religions of the world and bringing them into potential relation. Years later, asmaa continues to prioritize this relational metaphor and aesthetic, not because it illuminates the ethical mutualities that are already present, rather because it carries a latent desire for the solidarities to come. By bringing asmaa’s research into the fold of this series, her golden threads can be extended to stitch together the diversity of the projects included.

Intuition #3: Relation

Reflecting on his poetic intentions, Édouard Glissant writes: “By brute necessity we must start with what we know abruptly.”1 Ornamenting Relation is such an abrupt beginning of research through the entangled fields of ornament, relation, and intuition. This set aims to activate the concept of ornament as a potential site for relation, where diverse histories and aesthetics may come together. The golden thread moves across disparate landscapes and politics without breaking. How can a geometric flattening of the Kaaba speak alongside nostalgias for historical architectures in emerging nationalistic contexts? What can discussions of international residencies and comparative religion lend to our understanding of painterly mystifications and opaque textualities?

Owen Jones’s ambition to organize the ornamental impulse through the medium of print emerged out of a scholarly desire to introduce alternative aesthetics to the British public with the goal of modernizing (read: universalizing) British design. His project sampled a vast range of ornaments through visual excerpts and anecdotes. The result of his appropriative labour is a “mosaic of patterns, decontextualized and unnaturally homogenous,”2 one we are told represents an overview of the world’s urge for the decorative. Almost two centuries after the publication of The Grammar of Ornament, we seek to recuperate what was lost with a language of our own making. The works included in this set are strategically pulling from diverse locations so we can glimpse at the continuities and discontinuities in the use of the ornament, and how these reflect our attempts to form relations beyond the political and aesthetic borders set for us. This project is a visual manifestation of a desire for connection and intimacy through the figure and process of the ornament, one which opts for relation over homogeneity.

—Noor Bhangu

Ornamenting Relation

Curated by Noor Bhangu

Part of Crossings: Itineraries of Encounter, the 2021–22 Lightbox Program

Respondent Program

A discussion between asmaa al-issa and Noor Bhangu as part of Ornamenting Relation.

Attunement Session

Installation Views

Interpretive Video

Educator-in-Residence Shalon T. Webber-Heffernan leads a tour of Ornamenting Relation on University of Toronto Mississauga campus.

- Curator

- Noor Bhangu

She is a co-curator for Window Winnipeg (CA), a 24-hour art space for site-responsive presentations of contemporary art, with Mariana Muñoz Gomez and Jennifer Smith. Her independent curatorial practice includes projects: womenofcolour@soagallery (2018), Not the Camera, But the Filing Cabinet: Performative Body Archives in Contemporary Art (2018), Lines of Difference: The Art of Translating Islam (2019), Digitalia (2019/2020), even the birds are walking (2020), and Gives-on-and-with: Decolonial Moves of the Transcultural (2021).

- Attunement Session

- Golboo Amani

The Blackwood

University of Toronto Mississauga

3359 Mississauga Road

Mississauga, ON L5L 1C6

[email protected]

(905) 828-3789

The galleries are open. Hours of operation: Monday–Saturday, 12–5pm.

Holiday hours: regular gallery hours are in effect until and including Saturday, December 6. The galleries will then be closed for the holidays, except for regular hours on Saturday, December 13. In 2026, the galleries reopen Monday, January 5.

Facebook | Twitter | Instagram

Sign up to receive our newsletter.

The Blackwood is situated on the Territory of the Mississaugas of the Credit, Seneca, and Huron-Wendat.