If there were no borders, most of the people in this choir wouldn’t be here, and tens of thousands like them wouldn’t be risking their lives trying to cross the Mediterranean, scrambling over barbed wire fences in Ceuta trying to get into Spain, huddled on the rocks in Ventimiglia trying to get into France, crowded together in makeshift camps in Calais trying to get into Britain. In Europe, we think about borders and national anthems less and less, now that we can travel freely, now that our children can study in any university they want. But to millions and millions of people, national anthems still mean borders, and borders are a question of life and death, and that’s why we are here singing.

—Robert Elliot, Migrant Choir Project Coordinator

“Se lo Stato-nazione ha un’anima, essa è partorita da una metafisica dell’esclusione.”

[If the nation-state has a soul, it is born of a metaphysical exclusion.]

—Antonio Negri, July 2015

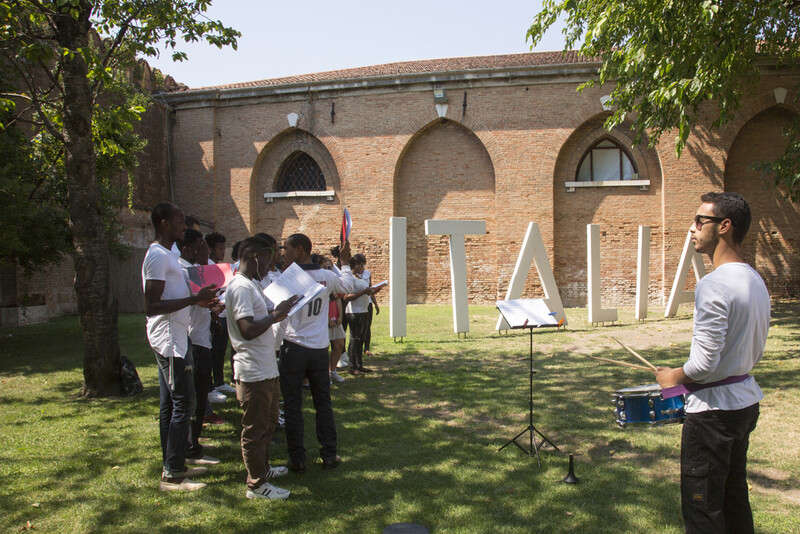

Inno Delle Nazioni, Migrant Choir is an action in which recent migrants to Italy, and their supporters, sing the anthems of Italy, France, and The United Kingdom in front of these respective national pavilions at the 2015 Venice Biennale. This performance is a speech act, in which non-citizens claim their rights of citizenship while rendering the exclusionary nature of these anthems visible.

Wars, state repression, and poverty have forced an increasing number of migrants from Africa and the Middle East to risk their lives, travelling from Lybia to Italy by sea. They await hearings in welcome centers in Sicily, are stranded at Ventimiglia on the French border, and are encamped in Calais, awaiting entrance to Britain. The European response to this humanitarian crisis has been cynical at best. Internal dissent has defeated even the modest proposal of accepting 60,000 refugees across Europe and inspired a hardening of European borders and enforcement procedures. In the province of Veneto, violent demonstrations recently erupted against a plan to house recent migrants in Treviso. In response, the President of Veneto and Northern League member, Luca Zaia, declared “No more refugees will be arriving” as a direct rebuke to the request by the national government’s proposal to settle migrants across the country and not only in the southern provinces.

The paths these migrants follow across Africa, the Middle East and Europe, trace backward the vectors of colonization that began in the late 19th century during the “scramble for Africa.” Eritrea, whose repressive military state has provoked the movement of the most refugees entering Italy this year, was an Italian colony from 1889-1941. Libya, the staging ground for voyages to Europe, was Italy’s colony from 1912-1947. Somalia, the country with the second largest number of refugees heading to Italy, was divided between Italy and Britain for the first half of the 20th century. The other nations from which the most migrants are escaping, were colonized by either the British—Nigeria, Gambia, Sudan—or the French—Syria, Senegal, and Mali.1 Syria, whose devastating civil war is source of the most global migrants today, was assigned to France as part of the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916, which gave the French control over Syria until 1946.

Colonization played an essential part in the constitution of the modern capitalist economy. Throughout the long process of what Karl Marx called “so-called primitive accumulation”, during which capitalism was formed, three novel lines transformed the globe: the borders of European nation-states, the enclosure of peasant lands as private property, and the subdivision of the world beyond Europe into colonies.2These lines may seem like artifacts of history, but these they act as foundations for the intertwined divisions that organize our world today.

The Venice Biennale was founded in 1895 as a celebration of Italian national arts, but it evolved quickly into an international biennale. By 1914, at the zenith of European Imperialism, there were seven national pavilions in the Giardini: Italy (1895), Belgium (1907), Hungary (1909), Germany (1909), Great Britain (1909), France (1912), and Russia (1914). The plan of the Biennale grounds with its two axes—the original Italian pavilion at the end of one, Britain flanked by France and Germany at the end of the other—has been built as an evolving representation of the balance of hegemony between national and colonial powers. The biennale itself functioned for much of its history as a project to assert the collective cultural supremacy of Europe over the rest of the world.

Europe’s national anthems were written between the 18th and 19th centuries. They are nationalist hymns, deeply ideological compositions designed to inspire common people to risk their lives to defend newly invented states. Often these simple songs point to the pure race of the nation, or allude to the conquest of neighbouring territories, or far off lands. The French Anthem, “La Marseillaise” (1792), calls repeatedly in the chorus for the spilling of impure blood. The Italian Anthem, “Il Canto degli Italiani” (1847) glorifies Scipio Africanus, the Roman general who conquered Carthage in 202 BC, recalling the Latin conquest of North Africa. “God save the Queen” (1744), the anthem of the United Kingdom, threatens to “scatter her enemies… confound their politics, and frustrate their knavish tricks.” These songs are refrains. Singing them draws a boundary in song, a line separating citizens from non-citizens. In 1862, Guiseppe Verdi was commissioned to write an orchestral work for the London World’s Fair; in response he wrote the cantata “Inno Delle Nazioni” (“Hymn of Nations”). His composition was written to describe world solidarity, yet combined only three national songs, those of Britain, Italy and France. This curation, designed to inflate the importance of Italy within Europe, appears in hindsight as a strangely prescient combination in relation to today’s struggles over migration.

In the context of contemporary events, it seems appropriate to sing these songs together again, in opposition to their original meanings. The lines that demarcate the edges of the nation-states, were drawn alongside the lines that subdivided the nation into private properties, and the lines that carved the world into colonies. It is precisely these exclusionary lines that are reinforced by the lines of words and music that form these anthems. But the act of singing them is politically expressive in ways that exceed the meaning of their lyrics, and the intended emotional effect of their scores. Singing is a line, which has great power to create social connections and affective responses. When many people sing together these lines intermingle, resonate and amplify, to create a kind of superlinearity.3This effect can be mobilized to defend the nation, but it also can forge solidarities across national lines, or in resistance to the idea of the nation as a closed territory. Inno Delle Nazioni, Migrant Choir, is an affirmation of citizenship as an act of self-definition. Citizenship is defined here not by the exclusive membership in a given national group, but as the act of demanding “the right to have rights.”4 But as migrants sing these songs their meanings self-implode and their exclusionary logics come undone.

The action is performed in solidarity with migrant rights organizations around the world.

—Public Studio (Elle Flanders & Tamira Sawatzky) and Adrian Blackwell

Songbook

Download the Migrant Choir songbook.

Migrant Choir

Presented in the context of the 2015 Venice Biennale and the Creative Time Summit, and staged in front of the British, Italian and French Pavilions.

Curated by Christine Shaw

Event Documentation

- Artists

- Public Studio

- Adrian Blackwell

- Curator

- Christine Shaw

Robert Elliot

Choir Conductor

Eugenio Sorrentino

Choir Members

Siham Adaim, Isaac Akhidenor, Adam Atik, Hamda Ben Rebeh, Moro Camara, Komedza David, Destiny Aifehesi, Lynus Osayande, Esther Osemi, Edith Jonah, Hamdi Gaaloul, Stephne Koumtozou, Tessy Louis, Kemi Ohomba, Salau Luqman, Uhunoma Enoma, Ogechi Obi, Koffi Marthe Sylveste, Favoor John, Abdou Wahab Diakhate, Adinou Yaovi Tokanou, Isabella Fregnani

Cittadini del Mondo Organizer

Carolina Peverati

The artists would also like to thank S.a.L.E Docks, Barbara del Mercato and Beppe Caccia for their support and encouragement.

The Blackwood

University of Toronto Mississauga

3359 Mississauga Road

Mississauga, ON L5L 1C6

[email protected]

(905) 828-3789

The galleries are open. Hours of operation: Monday–Saturday, 12–5pm.

Holiday hours: regular gallery hours are in effect until and including Saturday, December 6. The galleries will then be closed for the holidays, except for regular hours on Saturday, December 13. In 2026, the galleries reopen Monday, January 5.

Facebook | Twitter | Instagram

Sign up to receive our newsletter.

The Blackwood is situated on the Territory of the Mississaugas of the Credit, Seneca, and Huron-Wendat.